![]()

HISTORY OF BINGHAM

Trades and Crafts

The finds recovered by Felix Oswald in the 1920s and Malcolm Todd in the late 1960s through excavation at Margidunum enable us to reconstruct some aspects of the Roman economy over the 400 years of Roman occupation in this country. Although much of the consumer goods used on the site would have been locally produced, the initial military occupants imported some goods, which were not readily available in the vicinity and, after the military units left, a small town like Margidunum had access to a wide range of traded goods of some quality.

Felix Oswald put aside a room at the University where he studied and displayed the Margidunum finds. Here he is studying one of the complete pots (probably from one of the many wells he excavated). He was the first person to study Margidunum in the modern period.

Original picture in the Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Locally produced goods

Foodstuffs

Every day items such as meat, milk, eggs, bread and vegetables are most likely to have been obtained from farms in the surrounding countryside and perhaps brought in to sell in roadside shops. The “strip” buildings sited at right angles to the Fosse Way may have functioned in just such a way and one of them, Building B, had an oven situated behind it, perhaps for baking bread. Such shops can be seen depicted on carving from Ostia in Italy and have been found in excavation on larger town sites in England, such as Wroxeter.

An oven, possibly used

for baking bread, found behind Building B.

Photo: M. Todd. Nottingham University Dept Archaeology

Craftsmen

These are some of the hone stones from

the smith’s workshop. The middle one has been worn down.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

As well as perishable goods, craftsmen may also have set up shop along the Fosse Way. One area excavated by Malcolm Todd contained scrap iron objects, slag and a great number of sharpening hone stones used for sharpening tools. Todd suggested that this area perhaps functioned as a smithy. Lead slag was identified on Todd’s excavation, indicating the working of lead, perhaps from the Derbyshire mines. Fragments of lead sheet and a lead bowl were found during excavation, but lead has always been vulnerable to stripping and re-use so one can imagine that most of the Roman lead was reused during the Mediaeval period. Romans used lead for water tanks, pipes, bath liners and coffins or coffin linings (of which two were excavated by Todd in the Margidunum cemetery) and domestic items, such as small bowls. Several pottery vessels were found which had been mended using lead rivets and plugs.

These uninspiring looking lumps are fragments of iron slag of which a great number were found at Margidunum. They indicate that iron working was being carried out on the site.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

This crumpled bowl is made from lead rather than pottery and represents a number of objects, which the inhabitants of Margidunum would have had but which often do not survive for the archaeologist. Metal dishes were quite common and soldiers often had a metal bowl when on the march. However if they were damaged they could be melted down and recycled so they are not often found in excavations.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Distorted and over burnt pottery sherds together with a prop used to stack pottery in kilns are evidence that many of the pottery vessels used in the town were made locally. During the earliest military occupation of Margidunum, fine pottery was probably produced by potters attached to the army, coming from the Continent or the south of England. Thus the army was, in effect, importing potters rather than pots to facilitate the high standard of living to which they were accustomed. These potters produced a whole range of fine wares including fine orange wares imitating samian forms and tableware embellished with a mica rich slip, which made them glisten and look like their metal counterparts. A range of glazed pottery was found. Such vessels are rare and date to the late first and early second century. Glazed ware production is known outside the fort at Derby, but the fabric of this sherd is unlike the Derby glazed wares and may indicate production at Margidunum. This is a highly specialised technique, involving the careful control of temperature, and was certainly conducted by experienced potters from the Continent. At sites such as Wroxeter and Castleford, evidence for pottery shops has been found so we might imagine stalls set out selling both locally made and imported vessels.

A range of vessels probably made at Margidunum by the Romans. Clockwise from top left: two mortaria sherds, a fine white flask with red/brown painted stripes, a fine orange bowl fragment and a fine orange beaker covered in a white slip. The central sherd is from a white bowl with reddish brown painted decoration. Some of the vessels are very thin walled and were made by very skilled potters.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

This sherd comes from an orange jar, which was probably made near Margidunum. There are many like it from the site and it belongs to a group of jars popular in the second century.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

This jar is decorated using a technique known as roller stamping. A little roller was engraved with a pattern and then rolled around the leather soft pot before firing. This technique is known at second century potteries associated with the forts at Derby and Doncaster.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

This is a sherd from a cooking pot. This type of jar may have been made at Margidunum or close by and dates to the 1st AD. The rilling just visible as ridges on the body probably helped people not to drop it in slippy hands.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Other locally produced goods might include the many bone pins found during excavation.

A bone handle with oblique grooves which will increase the grip and are also decorative. The remains of an iron tang, possibly a knife blade, can be seen riveted between the two halves of the handle. The other two objects are antler off cuts found at Margidunum, which would have been made into similar handles or other items.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Many bone pins were found at Margidunum. These were used to secure the elaborate hairstyles favoured by Roman women and probably also to secure the loosely woven cloaks. Brooches would have been used to fasten more tightly woven materials.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Craftsmen such as stonemasons and woodworkers are represented by their tools and by their products. To these we can add builders, plasterers, thatchers and roof tilers. Roofers also used locally produced Swithland Slate from Charnwood. Fragments of window glass, together with a possible stone window arch implies the existence of glaziers. Keys from the site indicate the use of a locksmith. (all pictured below).

This piece of painted plaster gives

a tiny glimpse of the splendour of some houses at Margidunum. The wall paintings

have fallen off the walls as the building fell into disuse and, sadly, the weather

and the plough have broken up the fragments over the centuries so that it is

no longer possible to reconstruct the full design. Enough remains to suggest

coloured borders and stripes with some patterns.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Roman roof tiles, showing how they were

used. Note the concrete visible to the right.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth.

Roman roof slates brought to Margidunum

from Charnwood, Leicestershire. Very many of these came from the late house.

They are arranged here to form a diamond pattern, which is indicated by the

position of the nail holes in them.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Fragments of window glass were found

in both of the large-scale excavations at Margidunum and show that at least

some of the houses had the luxury of glazing. According to Roman writers, windows

were only available to the wealthy. Window glass was made by pouring molten

glass onto wooden trays and leaving to harden. The windows would have been quite

opaque compared to modern ones.

Nottingham University Museum. Photo: Robin Aldworth

This mattock would have been hafted

on a wooden handle. Look how similar it is to modern examples!

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Several boxfuls of Roman iron nails from Margidunum are stored in the Museum basement. These are rarely found on Iron Age sites but are very common on Roman forts and are sometimes found bent into a curve (as bottom right) where they have been removed to allow re-use of timbers. They represent a variety of timber structures, such as houses, fences and cupboards, which have rotted away.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Cottage Industries

Cottage industry may have included the production of various items of clothing. Site finds include spindle whorls and weaving tablets. These clearly would be used in the production of garments for a household, but we know from the Vindolanda tablets that some types of cloaks were traded and were sought after. Tablet 255 gives us a letter from one Clodius Super to Cerialis, prefect of the Ninth Cohort of Batavians at Vindolanda AD 97-105, asking him to send six sagaciae, saga and seven palliola and six tunics which he could not get hold of (at Vindolanda). Sagaciae, saga and palliola are different kinds of cloaks. Tablet 196 refers to casual clothing for dining. Accounting list such as that recorded on tablet 192 lists 38lbs wool as well as more cloaks and a bedspread.

Seven spindle whorls used as weights while spinning wool. These are an example of recycling and imaginative use of materials by the Romans. The top right red spindle whorl is a reworked samian base while the flat examples are made from domestic grey ware sherds.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

This domed spindle whorl has been worked from a piece of bone.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

For more on the Vindolanda tablets see http://vindolanda.csad.ox.ac.uk

Traded goods

Maps showing the parts of Britain and

the continent where imported goods came from can be seen by

clicking here:

Imports from the Continent

Trade within Britain

The military phase

Traded deli food

Some foodstuffs were traded including oysters. Oswald found a cylindrical mass of oysters stacked in overlapping circular rows as if in a wooden keg which had since perished. Oysters were a popular food with the Romans and many were found scattered throughout the excavation deposits. These would have perhaps come by road from the Lincolnshire coast. We know from elsewhere that quite exotic foodstuffs, such as figs, grapes and apricots could be obtained in Britain, but analysis of organic material was sadly not carried out at Margidunum.

Imported pots

This little beaker has

been decorated using a rough casting technique that

would help the beaker not to slip.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

In addition to on-site production of high-class pottery vessels made by potters who travelled with them, the army also imported quantities of table ware. The most popular of these was the shiny, red, samian ware used to make bowls, dishes, cups, jars and mortaria, a special type of bowl used for food preparation by the Romans. These came from Gaul and were carried by ship to the coasts of Britain from whence they were conveyed by road to the military and civil market. Stalls at Wroxeter and Castleford were found selling piles of samian bowls and it may be that similar stalls were set up by merchants in the settlements that grew up outside forts along the Fosse Way. Certainly, quantities of this fine pottery were found at Margidunum.

These shiny red bowls are imported from Gaul. This type of bowl with the flange was common in the 2nd century AD. It is not certain which part of Gaul these came from.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Fine red slipped samian ware mortarium, a kind of mixing bowl used to pulp and mash fruit and vegetables. This example comes from Central or East Gaul. The potter has made a spout in the shape of a lion’s head to pour off the liquid.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

As well as the large quantities of samian ware, smaller amounts of fine cups and beakers were imported from potteries in Central Gaul and the Rhineland, related to the samian production centres. Those found at Margidunum from Central Gaul include beakers with a curving pattern executed by trailing semi-liquid clay over the air-dried vessel and then letting it dry before dipping the whole pot in a liquid clay slip of a contrasting colour, red or brown/black. A second form found at Margidunum was a bowl with three little legs. At least three of this type were found but it is very rare in Britain.

These sherds are from fine vessels imported from Central Gaul round Lezoux and Martres-de-Veyres in the 1st and early 2nd centuries. The sherds come from elaborate beakers which have semi-liquid clay trailed over to form surface patterns, a bit like decorative icing, before being dipped in liquid clay, called a slip, which fires to a darker colour, brown or orange. The examples to the right have a rough coating of dried clay particles, called rough casting, scattered over their surfaces before being dipped in the coloured slip to create a different effect. The sherds at the top come from shallow bowls with three little feet, called tripod dishes.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

One example is decorated with rouletting, achieved by running a little decorated wheel around the pot while leather hard, a bit like decorating pastry. The other examples have rough-cast decoration. This technique involved coating the pot in little bits of dried clay before dipping in the coloured slip and firing it. This has a similar effect to pebble dash and, indeed, some pottery centres used sand rather than particles of dried clay to coat the vessel. A very fine cup may come from this area of Gaul also, although a precise parallel to the form has not yet been found.

This very fine black small bowl or cup comes from the Central Gaulish workshops around Lezoux, also making the more popular red samian ware. Some of the black slip beakers from Margidunum may also have come from here as well as other kilns around Trier in East Gaul.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Locally traded wares

Black ware used to make fine bowls decorated with stamps was found, dating to the late first or early second century. This belongs to a group known as Parisian ware, but the bowls from Margidunum seem to have very distinctive forms and decoration suggesting they may have been made nearby. Coarse wares seem to have been made locally also. At least one ware seems to have been made at Margidunum or very near by. Most of the cooking pots were in a grey ware, which was produced all over Roman Britain and can be difficult to identify the source. Further study of the coarse wares at Margidunum may uncover evidence of trade with the early kilns at Lincoln or Leicester.

A very fine black or grey pottery was produced around Margidunum during the late 1st to early 2nd century. These sherds are from bowls with stamped and rouletted decoration and would originally have been polished to a high sheen.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

A very fine black or grey pottery was produced around Margidunum during the late 1st to early 2nd century. These sherds are from bowls with stamped and rouletted decoration and would originally have been polished to a high sheen.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Three carinated (having a sharply angular neck) beakers in common grey ware. These are very common at Margidunum in the late 1st and 2nd centuries and are invariably 12-14cm in diameter as if the potters used some sort of template to standardise production.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

A local potter has made this attractive grey ware pot, probably in the late 1st or early 2nd century. The jar is rather barrel shaped and has raised cordons on the shoulder which the potter has decorated with little animals, possibly a hare or a dormouse (not a rabbit as they were not present in Britain at this date).

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

The Romans introduced a mixing bowl called a mortarium. These were large with hooked or hammer-headed rims and were made by specialist potters who, in the first and second century, stamped their name on the rims.

A range of sherds of mortaria brought to Margidunum from different potteries. Clockwise from top left: a white painted mortarium from Mancetter-Hartshill potteries near Coventry (3rd-4th century), a red coated mortarium from the Oxford potteries (4th century), two sherds from mortaria from potteries at St Albans (1st century), a locally made mortarium and one from the Swanpool kilns at Lincoln (late 3rd or 4th century. The animal head spouted mortarium in the middle comes from the Nene Valley kilns. The middle one on the left is a Mancetter-Hartshill spout.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

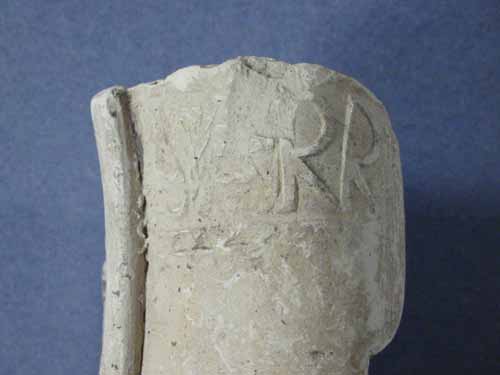

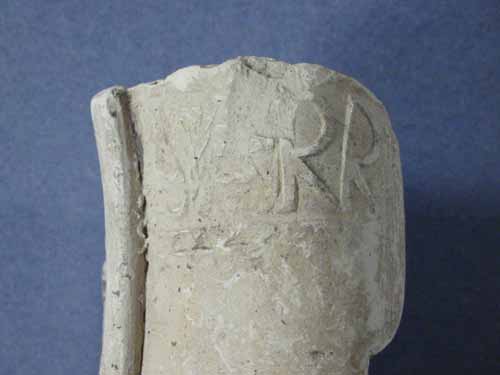

This mortarium is

from St Albans and is stamped by a man called Albinus

who worked there in the late 1st century having probably

moved from kilns at Colchester.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

During the early period, mortaria have been identified from potteries at Mancetter-Hartshill, near Coventry, and St Albans. Potters identified on mortaria found at Margidunum include Albinus who worked at St Albans and Sarrius from Mancetter-Hartshill. Another mortarium made by Albinus is stamped F LVGVDV, which probably means f(actum) Lugudu(ni), made at Lugudunum, presumably near St Albans. We also know of mortaria made by Matugenus, the son of Albinus, also working at St Albans. These mortaria are clearly linked with changes in food preparation and, interestingly, are found in much the same quantities on both rural and urban sites. We know from a mortarium from the Roman site at Usk marked for a military unit – “contu(e)rnio Messoris” - before it was fired that units within the army sometimes ordered these vessels straight from the potters. Graffito scratched on a samian bowl after firing from Rocester, marked Coh(ortis) … [G]allorum, and a mortarium from Catterick, inscribed “century of M”, suggests the purchase of pottery vessels on behalf of a company.

Making mortaria was a specialised skill involving the throwing of large heavy bowls and the attachment of heavy rims, specially shaped to make lifting the bowl easier. The potters of both samian and mortaria often stamped the vessels with their names of the names of their firms prior to firing the pots, probably as a sort of quality control. This mortarium is from Mancetter-Hartshill near Coventry and is stamped “Sarrius”, a well known potter working at Mancetter Hartshill in the mid-second century and also at kilns near the fort at Doncaster.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

This mortarium is from St Albans and is stamped by a man called Albinus who worked there in the late 1st century having probably moved from kilns at Colchester.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Other traded goods

Other items imported from the Continent include pipeclay figurines from the Allier region of Gaul and probably some of the fine glassware, although some of this may have been produced in Britain, at places such as Leicester and Wilderspool, Cheshire, where glassworks are known. A fragment of marble veneer was identified which probably came from the Continent and the stone pilaster of Lincolnshire limestone had also been imported to the site. Stone querns from Derbyshire were also very common.

These glass fragments are from delicate phials, cups and beakers, probably imported from the Rhineland (East Gaul) or made from imported recycled glass from the Continent.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Leather garments and shoes were also sometimes obtained from elsewhere. A shoe surviving at Margidunum was very decorative. In the Vindolanda tablets (no. 343), Catterick is mentioned as a source of hides, which presumably would have been used by the army to make tents, cloaks and many other leather items. Excavations at Catterick have suggested that it may have been a leatherworking centre for the army and the author of the letter surviving as tablet 343 may have been a trader dealing with the army.

The military and commercial function of Margidunum is reflected in the recovery of at least three imported samian inkpots and some iron styli. These would be used to compile inventories of the items stored in the camp or to write lists for military personnel to take to military depots such as that possibly sited at Margidunum at some stage. Such lists survive at Vindolanda.

Red ware (samian) inkpot. Sherds from several of these were found at Margidunum and, like the stylus. This tells us that there were educated people living there, probably officials in charge of taxation or the imperial post or the military quartermaster. Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth |

Romans used these iron spatulate objects, called a stylus, to write on wax tablets. The pointed end was used to inscribe the wax while the spatulate end was used to “rub out” mistakes. The presence of writing materials at Margidunum shows that some people were literate and perhaps indicates the presence of clerks and officials collecting taxes and working for the Imperial postal system. Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth |

The civil phase

Imported later wares

In the second century, fine samian ware continued to be imported to Margidunum although there is evidence that supply may have fluctuated and at times extensive repairs were necessary either because the owners could not afford a replacement or could not obtain one. Fine wares from Gaul are represented by these late second to third century fine black ware beakers and cup. However most of fine table wares from the middle of the second century were obtained from a large pottery in the Nene Valley producing a wide range of beakers, bowls and a distinctive lidded vessel known as a Castor Box. These fine wares were made in white or brown-orange clay, which had been dipped in a darker slip. They were decorated in various ways including en barbotine (relief decoration formed by trailing semi-liquid clay over pot when air dried), rouletting, and by painting and were widely distributed throughout the 2nd-4th centuries in the Midlands and beyond. In the fourth century, tableware was also obtained from kilns near Oxford, which produced fine bowls with a red colour coat, sometimes further decorated with white paint. There may also have been tableware and mortaria bought from a little nearer at the Lincoln kilns in the late third and fourth centuries. One or two fine samian bowls also came from Argonne in northern France in the fourth century.

This is a lovely beaker with a shiny greenish black coating. It was made in Trier, East Gaul, and imported to Margidunum in the late 2nd or mid 3rd century AD. Some examples have motto written in white around the body of the unindented beaker such as “Bibe me” Drink me or “DA MERVM” Give me unwatered wine!

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

This elegant bowl and lid formed a set

and was bought from kilns in the Nene Valley in the 3rd AD. It may have been

used as a soup tureen.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

These sherds show us the range of fine

tableware traded from the Nene Valley kilns. From top left clockwise: a late

2nd-3rd century scale indented beaker, the scales have been applied like pastry

roundels and then the whole beaker has been dipped in a darker slip before firing;

a small bowl with white arcs painted after the darker slip has dried, 4th century

AD; a late 3rd-4th century AD platter.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

These sherds come from fine red ware

bowls supplied by large potteries near Oxford, which became very popular in

the 3rd and 4th centuries. Mortaria were also bought from the Oxford kilns.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Argonne red ware imported from near Rheims in the late 3rd to mid 4th century. This sherd comes from a bowl decorated with a distinctive roller stamped geometric patterns. The roller would have been engraved to make a pattern and used on leather-soft clay before firing.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Other pottery vessels were obtained from potteries within Britain itself.

These rather rough sherds

of pottery have all been traded from other parts of

Britain, as far away as Dorset. From top left clockwise

a jar made near Belper, a bowl from Dorset, a jar from

Lincolnshire and a jar from Bedfordshire or south Lincolnshire.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

The military obtained large quantities of a black, burnished kitchen ware from Dorset and these must have been sold at settlements along the Fosse Way. These are often burnt or have burnt-on matter, presumably boiled over stew and such like. Cooking pots were not as easy to keep clean as metal or glass and may have been prone to cracking if moved from the fire onto a cold surface. There are certainly many broken pots represented in the debris left at Margidunum. Other coarse ware pots were obtained from Derbyshire, Lincolnshire and possibly Bedfordshire, perhaps traded for their contents rather than the pots themselves.

This bowl is from Dorset and the kilns

there produced thousands of jars and bowls in this ware for the army, distributing

them by sea up the coast to Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

This rough jar has a cupped rim to hold

a lid and comes from near Belper. This sort of jar was found traded as far away

as Scotland and was popular in Derbyshire and the surrounding area from the

mid 2nd century to the mid 4th century.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

This type of jar (called Dales ware)

was made in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire and was very popular with both the army

and the civilians there in the later 3rd and 4th centuries.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

This is a late jar type made in the

South Midlands, perhaps around Greetham in Lincolnshire or in Bedfordshire.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

In both the military and the civil periods of occupation, amphora containing wine and oil were brought from Spain in apparently quite small quantities if the Nottingham University Museum collection is representative. There are however quite a few large storage jars, made in shell-tempered ware, which may have been used to hold store liquids in the first and early second century. In the third and fourth century the frequent discovery of tall grey ware jars with narrow necks down the wells at Margidunum suggest that this type of vessel was probably used in a similar way to store liquid.

This fragment of pottery is part of

the rim of an amphora, a huge wine jar, from southern Spain. These are very

common in Britain from the 1st to 3rd centuries but are not very common at Margidunum.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Mortaria continued to be brought from the kilns at Mancetter-Hartshill throughout the second (including some made by Sarrius who worked at Mancetter-Hartshill and also opened up workshops at Doncaster and in Scotland), third and fourth centuries and these were augmented by samian mortaria, colour-coated mortaria from the Nene valley and Oxford, white slipped mortaria from Lincoln, and plain white mortaria from the Nene Valley. Locally made mortaria may be present in the second century but this needs further study.

Making mortaria was a specialised skill

involving the throwing of large heavy bowls and the attachment of heavy rims,

specially shaped to make lifting the bowl easier. The potters of both samian

and mortaria often stamped the vessels with their names of the names of their

firms prior to firing the pots, probably as a sort of quality control. This

mortarium is from Mancetter-Hartshill near Coventry and is stamped “Sarrius”,

a well known potter working at Mancetter Hartshill in the mid-second century

and also at kilns near the fort at Doncaster.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Here is a British copy (to right) of

the samian mortarium (to left). It was made at potteries in the Nene Valley

in the 3rd-4th centuries.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Trading and trade routes

These sherds are from

very large storage jars. They have combed arcs and lines

on their bodies perhaps to improve grip while lifting.

Many examples of this type of jar were found and some

have been found buried to the neck in the ground. Such

subterranean stores could be used to keep food cool

or, less attractively, to collect urine for tanning,

as was common practice in Mediaeval times.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

This far-reaching trade was facilitated by the excellent road and sea network established by the Romans. The Fosse Way leading from Exeter to Lincoln must have attracted traders as well as the imperial officials and soldiers for whom it was primarily built. Roman ship wrecks such as that at Pudding Pan Rock, three miles north of Herne Bay, Kent, give us an excellent idea of the kind of cargo coming to Britain and this included a consignment of samian ware, roof tiles and colour-coated ware. Other wrecks known from the Roman period were carrying amphora, mortaria and lamps. Shops within the settlements outside forts are known at Castleford, Yorkshire (with a stock of samian and Colchester mortaria), Corbridge on Hadrian’s Wall (stocked with mortaria and smaller amounts of grey coarse ware and samian) and in towns at Wroxeter (mortaria, samian and a small amount of whetstones). Trade in fine samian ware, mortaria, imported colour-coated wares, glass, lamps and other smaller consignments such as the hone stones is, therefore, certain. Coarse wares occur rarely in these shops, warehouse deposits and shipwrecks, but do occur at forts such as Corbridge. We know that local kilns were able to supply the needs of the civil population in the Romanised south of Britain while in the military north the pottery was obtained from military kilns outside the forts or brought in large consignments from places such as kilns in Dorset and the Thames estuary, where cooking wares known as black burnished wares were manufactured. Evidence of the types of pottery represented at Margidunum in the 2nd-4th centuries suggests local production of the common coarse wares and traded fine and coarse wares from Gaul, Lincoln, the Nene Valley, Oxford, Derbyshire, north Lincolnshire and Bedfordshire. It is difficult to quantify this trade but the samian supply certainly suggests fairly regular consignments arriving at the settlement with times of scarcity perhaps indicated by the need to repair rather than replace vessels.

These are some of the hone stones from the smith’s workshop. The middle one has been worn down.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Other traded goods

Roman brooches. These would originally have sprung pins and were used to fasten clothing as well as decoration. Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Other goods are less easy to source. Glass vessels were highly prized and certainly were present. There is some uncertainty as to whether raw glass was commonly made in this country, whether it was made from imported glass cullet (broken or glass waste collected and sold or bartered for re-use) or imported. Items of jewellery, such as brooches and shale bracelets, may also have been traded by itinerant traders whereas large scale consignments of tiles, stone and slate would have been delivered when the town wall was faced with Lincolnshire limestone and building was roofed with Charnwood slate.

These glass fragments are from delicate phials, cups and beakers, probably imported from the Rhineland (East Gaul) or made from imported recycled glass from the Continent.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

These fine objects are of shale and jet. The pin has a very fine facetted head and may have been used to secure an elaborate hair do or to secure a loosely woven cloak. Both the pins the bangles have been brought to the site from elsewhere in Britain, perhaps from around Whitby.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Roman roof tiles, showing how they were used. Note the concrete visible to the right.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth.

Roman roof slates brought to Margidunum from Charnwood, Leicestershire. Very many of these came from the late house. They are arranged here to form a diamond pattern, which is indicated by the position of the nail holes in them.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Additional information on Margidunum

Reports on the excavations carried out by Oswald and Todd and of investigations in the area by Trent and Peak Archaeological Unit contain much of the detail on which this account has been based. The main sources are:

1 Trent & Peak Archaeological Unit. Archaeology

of the Fosse way. Vol. 2 (held by Nottinghamshire Sites and Monuments

Records).

2 Todd, M. 1969. 'The Roman settlement at Margidumun. The excavations

of 1966-8'. Transactions of Thoroton Society 72.

3 Oswald, F. 1927. Margidunum. Transactions of Thoroton Society 31, 55-84.

4 Oswald, F. 1941. Margidunum. Journal of Roman Studies 31, 32-62.

5 Oswald, F. 1948. The Commandant’s House at Margidunum. University

of Nottingham.

6 Oswald, F. 1952. Excavation of a Traverse of Margidunum. University

of Nottingham.

7 T.D. Pryce. 1912. Margidunum: a Roman fortified post on the Fosse Way.

Journal of the British Archaeological Association 177-210.

There are many web sites with information about Roman Britain. Links to some are given in the text. For books on the subject log on to http://www.english-heritage.org.uk and check their catalogue